The Philadelphia Art Museum has opened a comprehensive exhibition exploring 100 years of surrealism, just one day after the institution's board made headlines by abruptly firing CEO Sasha Suda. The exhibition, titled "Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100," offers visitors an in-depth look at the influential art movement that originated in Paris in 1924 and quickly spread across the globe, fundamentally changing how artists approached creativity and consciousness.

Louis Marchesano, who has temporarily assumed day-to-day operations of the museum, declined to comment on Tuesday's shocking executive termination, instead focusing attention on the surrealist art collection. The exhibition presents an overview of the first 25 years of the surrealism movement, chronicling how it was almost immediately tested by the rise of European authoritarianism before being forced into exile across North and South America during World War II.

Surrealism emerged from the earlier dadaist movement and drew heavily from Sigmund Freud's groundbreaking studies of the subconscious mind. However, its official birth can be precisely dated to October 15, 1924, when poet André Breton published "The Surrealist Manifesto." This revolutionary document embraced irrationality and dreams as pathways to unlock human creativity. "There exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imagined, past and future, the communicable and the incommunicable, high and low, cease to be perceived as contradictions," Breton wrote in his manifesto.

Curator Matthew Affron emphasized that Breton did not invent surrealism but rather was the first to articulate it as a revolutionary philosophical act. "Breton codified a philosophy of life, a way of living, a way of being," Affron explained. "It's about using all sorts of methods rooted in the history of poetry, in the history of art, in the influence from Freud's psychoanalysis, in radical politics – all coming together in the manifesto as a statement about changing the way you see the world. What surrealism wanted, fundamentally, was a revolution in consciousness."

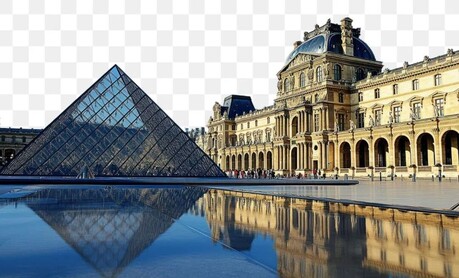

"Dreamworld" is a traveling exhibition that has previously been displayed in Belgium, France, Spain, and Germany, with Philadelphia serving as its fifth and final destination. Each museum has curated the exhibition individually with different artworks, and approximately 35 pieces in the Philadelphia Art Museum's version come from its own collection. The museum's particularly strong surrealist holdings can be attributed to major donations in the 1950s from avant-garde art collectors Walter and Louise Arensberg, as well as Albert Gallatin.

The exhibition features approximately 180 works that demonstrate surrealism extends far beyond the popular imagery of melting clocks or green apples wearing bowler hats. For advocates like Breton, surrealism was not merely a style or technique but rather an inquiry into subconsciousness that required artists to essentially fool their own brains to arrive at mental states similar to psychosis. The show includes works by André Masson, who employed automatic drawing by making marks with no clear intention to see how they would work together. Spanish artist Joan Miró created sketches completely disconnected from reality as the foundation for abstract paintings such as "The Hermitage" (1924).

One particularly fascinating aspect of the exhibition is its collection of "exquisite corpses," folded paper collaborative drawings that represent a communal technique. This method involved breaking down a figure into several parts, with each artist drawing a section without seeing what others had created. The results were typically discordant, monstrous chimeras that no single artist could have intentionally envisioned. "This idea of finding a technique which evades your conscious control is really the central part here," Affron noted. "It's what makes the exquisite corpse such a famous and emblematic type of surrealist work."

By the 1930s, surrealist techniques and philosophies were well-developed when world events began challenging their fundamental sensibilities. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, followed almost immediately by World War II, marked the rise of European authoritarianism – the complete antithesis of surrealism's socialist roots. The playful monsters of irrationality that artists had nurtured during the 1920s were suddenly unleashed to represent the brutal realities of war. Affron points to Max Ernst's "The Fireside Angel" (1937) as one of the most significant pieces in the exhibition, depicting a multicolored, hybrid animal of indeterminate species engaged in what appears to be an ecstatic yet terrifying dance.

"A monster exemplifies the idea in surrealism of surprising juxtaposition as an incredibly strong creative tool," Affron explained. "Monsters return in the 1930s when surrealist artists are looking for a way to react to the terrifying political and social developments of the time." Salvador Dalí's "Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War)" powerfully demonstrates this evolution, showing a semi-human colossus literally tearing itself apart.

During World War II, many surrealist artists from France and Spain fled Europe and found safe haven in Mexico and the United States. In these new environments, surrealist approaches to art began spreading among artists who did not necessarily consider themselves surrealists. The exhibition includes a small but significant painting by Frida Kahlo, "My Grandparents, My Parents, and I" (1936), which shows the artist as a young girl connected to her ancestors by a red ribbon. While Kahlo never subscribed to Breton's manifesto, he considered her work authentic expressions of surreality, once famously declaring that "Mexico is the most surrealist country in the world."

The exhibition also features several early works by American artists who later became foundational figures in abstract expressionism, including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and Arshile Gorky. Pollock's "Male and Female" (1942) was created shortly after the artist underwent Jungian psychoanalysis, and the symbolism in the painting likely derives from Jungian dream studies, with marks that appear to come from automatic drawing techniques.

Among the exhibition's more unusual pieces is Wolfgang Paalen's "Articulated Cloud," a replica of a 1937 sculpture consisting of an umbrella made entirely of sponges, hanging above his other works from the 1930s created before his exile to Mexico. The show also features Salvador Dalí's famous "Aphrodisiac Telephone," which welcomes visitors to a room filled with erotic surrealist art, with the title alluding to the lobster's reputation as an aphrodisiac when consumed.

As Affron emphasizes throughout the exhibition, "There is no such thing as a surrealist style. Any method counted as a good method if it could accomplish the underlying aim of breaking down that barrier between the conscious and calculating part of the mind, and the unruly, unconscious spontaneous, maybe scarier part." This philosophy is evident throughout the diverse range of works on display, from Joseph Cornell's intricate shadowboxes to Max Ernst's "Chimera," all demonstrating the surrealists' use of nature imagery to create impossible landscapes and impossible beasts.

"Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100" will remain on view at the Philadelphia Art Museum from November 8, 2025, through February 16, 2026, offering visitors an unprecedented opportunity to explore how this revolutionary art movement continues to influence contemporary culture and artistic expression more than a century after its inception.