When the Saja Boys captured audiences' hearts with their distinctive style in Netflix's hit animated film "KPop Demon Hunters," many viewers were curious about the wide-brimmed hats adorning the characters' heads. These traditional Korean hats, called "gat," were once essential accessories for men appearing in public during the Joseon era. However, master craftsman Chung Choon-mo, who holds the Intangible Cultural Heritage title for gannil (the art of gat making), believes the film missed a valuable opportunity to honor Korea's rich cultural traditions.

"'Gat' is more than just a hat," explained Chung during a recent interview at his studio at the Korea Heritage Agency in Samseong-dong, Seoul. "Historically, it represented a man's respect for etiquette, his sense of honor and ceremonial awareness, similar to how men today might wear a suit for formal occasions to show respect or dignity." The 84-year-old master, who has been crafting these traditional hats for 67 years, emphasized that gat served as symbols of men's status, pride, education, and honor in Korean society.

During the Joseon era (1392-1910), hats were far more than functional accessories or style statements. Every man's outfit required a hat that indicated his social status, profession, and the nature of the occasion he was attending. Unlike today's hats, which primarily serve to shield from the sun or complete a look, gat carried deep cultural significance that reflected the wearer's place in society and his adherence to proper social conduct.

Chung expressed disappointment about how traditional items like gat are often misrepresented or overlooked in contemporary dramas and movies. "The tradition and significance of such items are often overlooked in dramas or movies, and it is a little disappointing," he said. "It makes me feel as if the traditions and aesthetics of men's attire are slowly disappearing. Now, Koreans rarely see the hats in real life, and even less try them on."

What makes gat particularly special is its uniqueness to Korean culture. "Gat is unique to Korea. There is nothing equivalent in Western cultures or nearby Asian countries," Chung noted. "Apart from Confucian values, it also served as a visible expression of how a person should live properly and honorably in society." This distinctive cultural artifact represents centuries of Korean craftsmanship and social values that cannot be found elsewhere in the world.

The master craftsman also pointed out a common problem in film and television productions. Traditional hats featured in these shows are typically inexpensive versions made from modern materials like PVC or nylon, rather than authentic bamboo and horsehair used in traditional gat making. While budget constraints may explain this choice, Chung argued that using genuine gat, even if rented, would better convey the cultural and historical significance of these remarkable items.

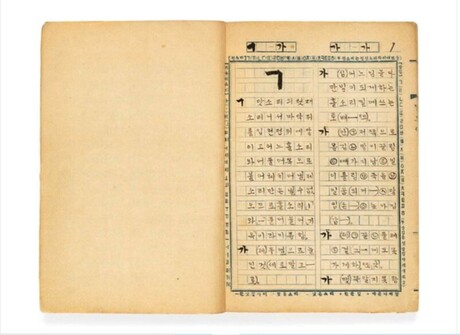

In his workshop, surrounded by carefully organized stacks of bamboo strips, silk fabric, and lacquer waiting to be transformed into perfect gat, Chung highlighted a particularly special type called "jinsarip." This premium bamboo hat features an exceptionally delicate brim constructed by layering fine bamboo strands three or four times. The creation process requires masters to use heated irons to fuse silk threads individually, combining precision with artistry to achieve a flawless finish.

The gat-making process begins with shaping the crown, known as "chongmoja." Thin bamboo threads called "juksa" are carefully woven and secured using heated irons. Next, the flat "yangtae," or brim, is expertly molded before final finishing touches are applied. For enhanced aesthetic appeal, decorative paper embellishments called "jeonggot" and "eungak," made from hanji (traditional Korean paper), are added inside the crown's frame. Around the junction where the crown meets the brim, a braided silk thread is carefully attached as the final touch.

"This type of hat was typically worn by kings and noblemen, highlighting its status as a symbol of authority and prestige," Chung explained about the jinsarip. "It usually takes a year to make this, and the one that I made last year is by far my favorite piece of art. It would be nice to see this on the screen. Or should I say the 'real gat'?" His confidence in his craft stems from decades of dedicated practice and recognition of his exceptional skills.

Chung's expertise isn't merely claimed but officially recognized. He began learning gat making in 1958 and was designated by the government as Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 4 in 1991. He followed in the footsteps of his three mentors – Ko Jae-gu, Mo Man-hwan, and Kim Bong-ju – who became the first gat makers to receive this prestigious title in 1964 in Tongyeong, South Gyeongsang Province.

Tongyeong, the small coastal city where Chung is based, has been renowned since the Joseon period for its many crafts that were supplied to the royal court in Seoul, with gat being among the most prized items. By 1973, Chung had become the sole remaining apprentice learning this ancient craft from the masters. The two other young apprentices who had started alongside him quit shortly after beginning their training, unable to see a promising future in this traditional art form.

The challenge of preserving this cultural tradition became deeply personal for Chung. "None of my teachers wanted their children to carry on the tradition because they knew it had no promising future. But I was afraid these skills would disappear," he recalled. This fear motivated him to continue despite the uncertain prospects, ultimately becoming one of the few people keeping this ancient craft alive.

With only a handful of artisans still practicing gat making, Chung has called for increased government support to preserve this vanishing cultural tradition. "I am trying to preserve gat with heart and skill, but government officials are out of touch, and at times, it feels like they do not truly understand or appreciate what I am doing," he emphasized, expressing frustration with the lack of adequate support for traditional crafts.

While acknowledging that holding exhibitions and allowing people to experience hat-making could help promote Korea's traditional headwear in the short term, Chung stressed that such measures are insufficient for long-term preservation. The survival of this irreplaceable cultural heritage requires more substantial commitment and understanding from both government officials and the general public to ensure that future generations can appreciate and learn from Korea's rich artisanal traditions.