A groundbreaking new book explores how artist Ruth Asawa and her circle of Bay Area women modernists revolutionized the relationship between motherhood and artistic practice in the mid-20th century. In 2008, when the author gave birth at home to her second child, instead of marveling at the baby's vernix-covered scalp and the fact of being born in the caul during a full moon, she experienced an extended anxiety attack, convinced she wasn't a good enough feminist to be a good mother to this baby she thought at the time was a girl. This experience led to a personal reckoning - in order to love and parent her children, she had to love and accept herself - and forced a shift in her art practice toward short bursts of feminist performance that she could accomplish after bedtime. It's with this and many other experiences in mind that she approached Jordan Troeller's new book "Ruth Asawa and the Artist-Mother at Midcentury" (2025), which examines the community of Bay Area women modernists around Asawa in the 1950s and 60s, including Merry Renk, Beth Van Hoesen, Sally Byrne Woodbridge, and Imogen Cunningham. Asawa and her circle didn't make work about motherhood; they made work while mothering. Troeller argues that by using the rhythms of the domestic as organizing principles and forging an interdependent care and creative community, and despite prevailing ideas of the modern male genius alone in his studio, these women modernists transformed motherhood into a medium. A 1970 photograph shows Sharon Litzky and students working on the Alvarado mosaic mural at Alvarado Elementary School in San Francisco, part of a pedagogical program founded by Asawa and Woodbridge. While the author questions whether motherhood functions as a medium in and of itself - noting it's certainly an art, perhaps best understood as endurance art - she found great value in reading about Asawa's art practice while raising six children and making work not in a standalone studio but in the house where they lived together. Troeller presents the lives and practices of artist-mothers who nurtured children, creativity, and communities simultaneously. The book is organized into three parts: Household Objects, Metaphors of (Pro)creation, and Caretaking in Public. The first section usefully delves into the artists' chosen materials, such as paper and wire, that had no fumes and were thus not dangerous to children and compatible with nurture work. Troeller writes that Asawa was someone in constant dialogue with fragility, dependence, and vulnerability. Interruption and responsiveness are not just conditions of childcare and time and space, Asawa affirmed, but of creativity and generativity. The skills of keeping a human alive are inherently artistic. A 1956 photograph captures choreographer and dance instructor June Lane Christensen and her students with Ruth Asawa's sculpture "Untitled S.437" (1956) in Santa Barbara. Imogen Cunningham, a photographer who was many years Asawa's senior, is a major focus in the book's second section. In one arresting spread, readers see her portrait of Gertrude Stein from 1935 across from her similarly posed portrait of Ruth Asawa from 1975 - both portrayed as titans, imposing figures at the height of their powers, Troeller writes. Troeller also beautifully connects the technique of repetition in their work; Asawa's rows and rows of looped metal echo Stein's "a rose is a rose is a rose." Asawa's belief that "you can only learn by doing" guides the third section, which focuses on arts education and art making as community care. She wanted an artist in every public school and spent a decade working on a pedagogical experiment called the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, now known as the San Francisco Arts Education Project. The author appreciated the amount of space Troeller dedicates to baker's clay - the flour, salt, and water concoction that hundreds of students used to make self-portraits, and that Asawa used to model what would become her Hyatt Fountain. In this way, Troeller gets to the heart of something extraordinary: motherhood not as a biographical horizon but as a relationship to artistic materials, a feature of artistic self-fashioning, and a condition of reception. As the author notes, her hours on the kitchen floor making slime are part of her aesthetic; she knows this, yet still loves to see it reflected back at her. A 1974 photograph shows children working on the Stitchery Mural at Hillcrest Elementary School, led by Nancy Thompson and Ruth Asawa as part of the Alvarado School Arts Workshop. Like Hettie Judah and other authors in recent years, Troeller uses the term "artist-mother" rather than "mother-artist," and shows how reciprocity and caretaking become the work itself, not just the subject or the conditions. For art and children to survive and sometimes thrive, the author depended on multiple interconnected systems: a child care co-op in Williamsburg where they sometimes breastfed each other's babies, and another one later in Jackson Heights, a shared garden with shared childcare responsibilities, an Upstate commune for three weeks every summer, a few years of collaborative performance work with No Wave Performance Task Force, curator-mothers who understood the work, two residencies at the Museum of Motherhood in St. Petersburg, and dozens of art moms near and far to commiserate with and challenge and hold and love. Troeller has crafted a lucid and playful portrait not of a singular artist, but of an artist among other artists. This deeply researched and insightful book models non-patriarchal forms of both making art and narrating its history, reminding readers that taking care of children and making art - be it public art, community work, with children, or for children - are radical acts of parenting and anti-totalitarian making. "Ruth Asawa and the Artist-Mother at Midcentury" (2025) by Jordan Troeller is published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press and is available online and through independent booksellers. The book represents a significant contribution to understanding how women artists have historically navigated the intersection of creative practice and motherhood, challenging traditional narratives about artistic genius and the conditions necessary for creative work.

Latest article

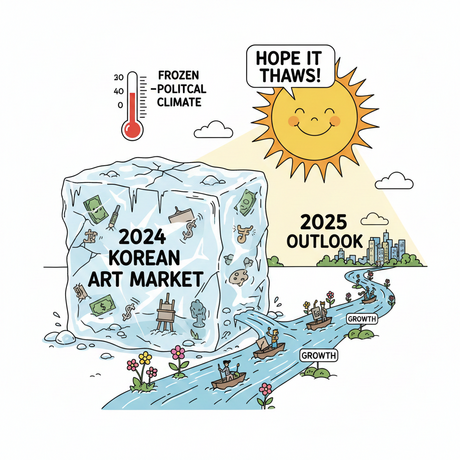

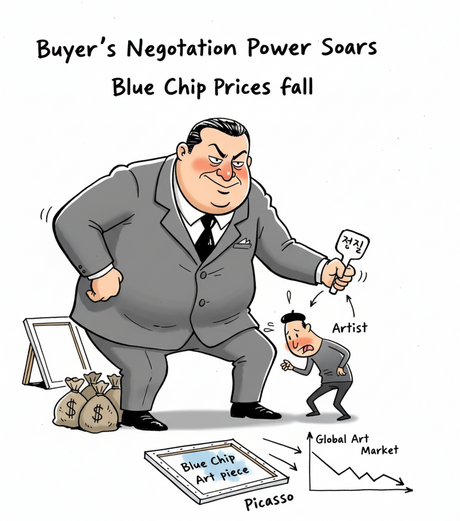

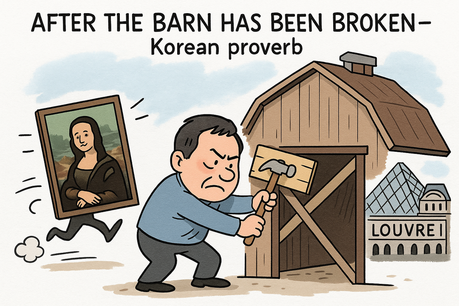

- Frozen Politics, Frozen Art: Hoping for a Thaw in Korea’s Art Market Next Year

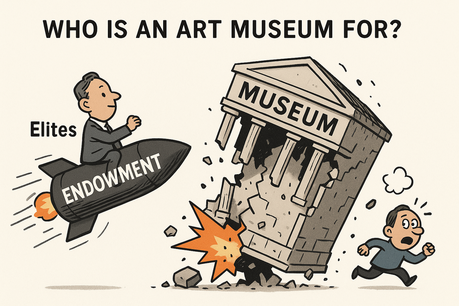

- Boom or Mirage? National Museum of Korea Debates Paid Admission Amid K-Culture Surge

- Billboard Names K-Pop as a Defining Force in 2025 Pop Culture

- Diagnosing the Global Art Market in 2025: Between Correction and Reconfiguration

- Korea Sets New Tourism Record as Inbound Visitors Hit 18.5 Million in 2025

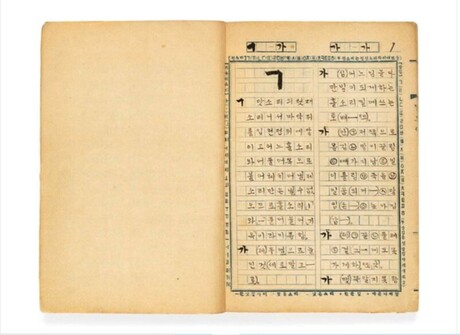

- NFM Releases Landmark Report on Village Beliefs Across Gangwon: Which Spirits Protected These Mountain and Coastal Communities?

- Online Poster Comparing Cho Jin-woong to National Heroes Sparks Backlash

- Why Lee Byung-hun Deserves to Win the Golden Globe