A groundbreaking exhibition at the Heide Museum of Modern Art brings together two influential photographers from different continents and artistic movements, revealing unexpected connections between Surrealist pioneer Man Ray and Australian modernist Max Dupain. Running from August 6 through November 9, 2025, the exhibition features over 200 prints, archival materials, and artist books, primarily from the transformative decades of the 1920s and 1930s.

The timing of this comprehensive survey feels particularly significant, as it has been more than two decades since Man Ray received substantial exhibition attention in Australia. His last major showing was the touring exhibition "Man Ray" at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2004, curated by Judy Annear and Emmanuelle de l'Ecotais. Similarly, Max Dupain's last major solo exhibition, "Max Dupain: Modernist," took place in 2007, though his work continues to be displayed at the State Library of New South Wales, which houses his commercial photography archive.

The exhibition's concept stems from a fascinating historical connection discovered in archival research. In 1935, Dupain was commissioned to review Man Ray's artist book "Man Ray Photographs 1920-1934" for The Home, a popular Australian lifestyle magazine. In his review, Dupain wrote with remarkable prescience: "The importance of Man Ray in photography is analogous to that of Cézanne in painting, and it does not seem imprudent to prophesy his enjoyment of an equivalent greatness." He concluded by describing Man Ray as "a pioneer of the twentieth century who has crystallized a new experience in light and chemistry."

Co-curators Lesley Harding and Emmanuelle de l'Ecotais have structured the exhibition to avoid the typical center-periphery narrative that might position Paris as the cultural hub and Australia as a distant outpost. Instead, they present both photographers as equals, drawing inspiration from Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson's "UnAustralian Art" project, which argues that Australian art belongs to and is part of the global art world. This approach allows visitors to see how modernist photography emerged simultaneously across different geographic and cultural contexts.

The exhibition's innovative V-shaped mirrored layout encourages visual comparisons while deliberately intermingling works by both artists rather than segregating them. This curatorial choice creates moments of productive confusion, where viewers find themselves darting back and forth to identify which artist created which work. The hanging strategy uses grids and loose clusters with group captions rather than individual wall labels, forcing more engaged looking and sometimes leading to mistaken attributions that illuminate the artists' shared visual language.

One of the exhibition's most compelling sections focuses on solarization, a technique that Man Ray and Lee Miller developed together in 1929. The process involves briefly switching on the darkroom light during exposure, introducing chance directly into the photographic process. Four of the six prints in this section are by Dupain, who began experimenting with the technique around 1935, using shells, lilies, daffodils, and eggs as subjects. Works like "Hera Roberts" (1935) and "Homage to Man Ray" (1937) make Dupain's debt to the American artist explicit, though wall text clarifies that Dupain was more interested in technical experimentation than in Surrealism's psychological and unconscious aspects.

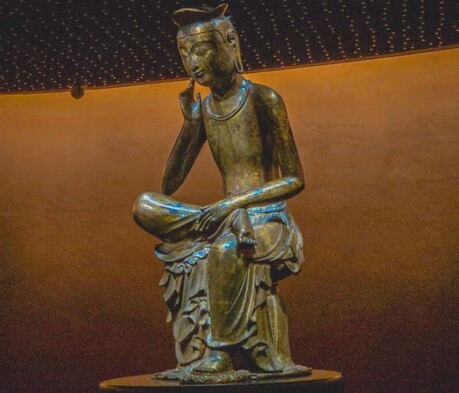

A dedicated room flanked by heavy velvet curtains showcases photograms, or camera-less photographs, created by placing objects directly on light-sensitive paper. Man Ray, who coined the term "rayograph" for his experiments, mastered this technique with confidence and assurance. His album "Champs délicieux" (1922), displayed in a vitrine, represents the culmination of a year during which he produced nearly 100 rayographs. Identifiable objects in his works include matchsticks, a print roller, razor, egg grater, metal coils, springs, and pipes, while other forms appear more translucent and mysterious.

The exhibition addresses the challenge of presenting women artists in what is billed as a two-person show between two men through a deep-rose-colored side room titled "Collaborators." Here, Lee Miller and Olive Cotton are presented as both central and marginal figures, practitioners and subjects for Man Ray and Max Dupain respectively. Miller's inclusion feels organic given her deep artistic and personal relationship with Man Ray, serving as both model and collaborator. Her fashion and commercial photography, including a striking 1930s Chanel advertisement, speaks directly to similar work displayed elsewhere in the exhibition.

Cotton's presence proves more complex, as she was not directly influenced by Man Ray and actually disliked the kind of disarray that characterized Surrealist experimentation. Represented by twelve prints, including a photogram paired with one by Dupain, her inclusion seems intended to broaden the frame of Australian modernist experimentation and remind viewers that Dupain's modernism never developed in isolation. Her work, characterized by order and precision, provides an interesting counterpoint to the exhibition's celebration of chance and experimentation.

The exhibition's emphasis on vintage materials and silver gelatin prints adds considerable impact to the viewing experience. While some works are posthumous prints from the 1970s and 1980s, the presence of more vintage photographs than expected makes them feel precious in today's era of digital circulation. Particularly striking is a 1933 print of artist and model Meret Oppenheim by Man Ray, whose metallic sheen glints under gallery lighting due to the silvering-out process, where metal migrates to the surface as a visible sign of degradation that becomes unexpectedly beautiful.

Close examination reveals intimate traces of the artists' hands: Dupain's scrawled handwriting in green pen on his 1938 "Surrealist Portrait of Miss Margery Nall" and framing marks visible on Man Ray's "Self Portrait" (c. 1930). Details that never translate in digital reproduction become apparent, such as the carefully drawn eyebrows of Kiki de Montparnasse in "Kiki with African Mask" (1926). The smallest work in the show, hung low and measuring only a few centimeters across, is Man Ray's beautiful portrait of Dora Maar (1936), where her curved hand partly obscures her face while a small porcelain hand rests at her throat.

Quieter correspondences emerge throughout the exhibition beyond obvious technical similarities. Both artists shared fascinations with reflection, repetition, and the use of sculptural doubles as recurring props. Dupain's "Discobolus and the Machine" (1936) and Man Ray's portrait of Dora Maar, made in the same year, demonstrate products of a shared visual language emerging in parallel rather than through direct influence. These works represent convergences of form, style, and iconography that point to similar preoccupations across geographic and cultural distances.

The current revival of interest in both artists extends well beyond the Heide Museum's walls. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is currently presenting "Man Ray: When Objects Dream," revisiting his paintings, sculptures, and rayographs, while his 1924 photograph "Le Violon d'Ingres" fetched an extraordinary $12.4 million at auction earlier this year. In Australia, the National Gallery is preparing a touring exhibition pairing Max Dupain with Ansel Adams, the State Library of New South Wales will soon present a Dupain solo exhibition, and the National Gallery of Australia's "Olive Cotton and Her Contemporaries" brings Cotton into conversation with international modernists including Dora Maar and Lucia Moholy.

This wave of renewed attention suggests something more significant than mere nostalgia for modernism's clean lines and optical games. The exhibition's clusters, wall arrangements, and mirrored correspondences reveal a logic of exchange between artists who never met, presenting their work not as cultural baton-passing but as genuine dialogue. What emerges is less a revival of modernist heroes than a recalibration of modernism's geographies, showing how the modern movement did not radiate outward from a single center but circulated sideways, adapted, and refracted across different cultural contexts.

The spirit of publications like "Photographie," the avant-garde French photo magazine that helped circulate Man Ray's work to Australian audiences through "The Home" magazine, returns in this 2025 exhibition. The revival represents not just a rediscovery of icons but a reimagining of where and how modernisms emerged, emphasizing shared contexts rather than mere cultural reception that gave rise to distinct yet resonant artistic articulations across continents.