Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are making massive investments in contemporary art as part of ambitious cultural transformation programs aimed at asserting global relevance and soft power influence. The compass needle of the art world is now pointing toward the ancient Silk Road, with a flood of new museum openings, freshly renovated cultural heritage sites, and art biennales sending clear signals to the international press about these post-Soviet nations' cultural ambitions.

The art world's shift is exemplified by the inaugural Bukhara Biennial in the historic center of the UNESCO World Heritage city in Uzbekistan. The exhibition offers foreign audiences saturated with the current over-politicization of art something entirely different: carefree, sensual, and almost dreamlike experiences. American curator Diana Campbell has titled her Bukhara Biennial "Recipes for Broken Hearts," bringing together international artists with Uzbek master craftsmen months before the September opening to create collaborative works on-site.

The setting resembles an orientalist fever dream, with poetry and music performances during full moon nights along the ancient Shahrud Canal, bathed in the sandstone colors of architecture that is sometimes a thousand years old. Sounds emerge from the vaults of former caravanserais, while artists like Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser have stretched hand-woven textiles in labyrinthine patterns over waterways. Subodh Gupta constructed a domed building entirely from enamel bowls, where food is prepared on certain days. The biennial's title references an Uzbek legend about a hearty dish that was supposed to heal a prince's broken heart, making Campbell's art show both balm and guilty pleasure.

Under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan has undertaken an ambitious cultural transformation in post-Soviet Central Asia, primarily financed by the state Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF), which also funds the Bukhara Biennial. The boldest demonstration of power by the Mirziyoyev government to date is the new State Art Museum, scheduled to open in the capital Tashkent in March 2028. This mammoth building is intended to become Central Asia's largest exhibition space, encompassing more than 430,000 square feet of usable area, with about 91,000 square feet dedicated to exhibitions. The building is being designed by Japanese star architect Tadao Ando and Stuttgart exhibition design specialist Atelier Brückner, and will be constructed by Chinese construction giant CSCEC International.

Much smaller is the newly opened Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA) in Tashkent, whose artistic direction is being taken over by Sara Raza, a former curator from New York's Guggenheim Museum. The converted 1912 industrial complex is Central Asia's first institution dedicated solely to contemporary art, also financed by the ACDF. The foundation is currently renovating numerous museums throughout the country and having another built in Bukhara by internationally celebrated architect Lina Ghotmeh.

What drives Uzbekistan to invest so heavily in contemporary art? The landlocked country, rich in natural resources, has money and has been a partner in China's Belt and Road Initiative since 2015, participating in the multinational infrastructure program. Two of the main routes run through Uzbekistan, as do all four corridors of the gas pipeline between Central Asia and China. Furthermore, Uzbekistan is opening up to the world market and becoming increasingly interesting for European companies. According to the World Bank, Uzbekistan's GDP grew by 6.5 percent in 2024.

However, human rights issues remain in the country, though the art world is not exactly known for its integrity in this regard, with Art Basel now also expanding to Qatar without concerns. According to a recent report by the NGO Freedom House, Uzbekistan is classified as unfree. Under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, opposition parties and free assemblies are not tolerated, and state-controlled media, judiciary, and legislature largely function as instruments of the executive branch. There is no freedom of expression, and torture in detention is common.

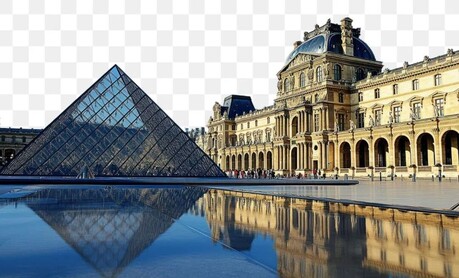

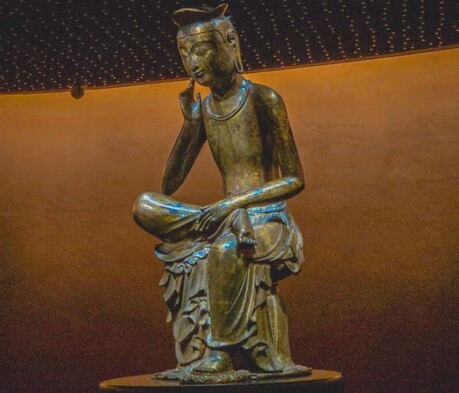

When Mirziyoyev took office in 2016, he announced reforms and established the ACDF in 2017. The foundation has since been active internationally: suddenly Uzbekistan is present at the Venice Biennale and lends its archaeological treasures for exhibitions at the Louvre in Paris or Berlin's James Simon Gallery. The predominantly Sunni Muslim country is also strengthening its connections to the Middle East, participating in the first Biennial for Islamic Art in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in 2023 and presenting itself at the Architecture Triennial in Sharjah.

While Uzbekistan's international cultural goals are openly pursued by the government, in its northern neighbor Kazakhstan—Central Asia's largest economy—wealthy businesspeople are primarily the driving force. In September, two major art institutions opened almost simultaneously in the capital Almaty: the Almaty Museum of Arts (AMA), financed by gas and retail magnate Nurlan Smagulov, and the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture by businessman Kairat Boranbayev. The AMA is a glittering new building colossus for Smagulov's private collection, which he claims he wants to transfer to the state. Sculptures on its forecourt by international luminaries like Alicja Kwade, Jaume Plensa, and Yinka Shonibare show from the outside that Smagulov wants to make an impression with global ambitions and curatorial strength.

But what does private property mean in Kazakhstan, which is formally a democratic republic but in practice a hybrid regime with authoritarian features, also classified as unfree by Freedom House? The story of Kairat Boranbayev raises eyebrows: in 2023, he was sentenced to eight years in prison and forced confiscation of his assets for embezzlement and money laundering related to gas imports. After voluntarily transferring assets to the state, Boranbayev was released. The Tselinny art center claims to the press that it is not affected by its financier's situation.

The former cinema building, built in 1964 under Khrushchev, was a beacon of Soviet modernism that became a nightclub after the collapse of the USSR, then a wedding venue, then a ruin. British architect Asif Khan and his wife, Kazakhstani architect Zaure Aitayeva, have now converted it into an airy architectural sculpture. Its concrete facade is folded like a pleated skirt and decorated with motifs based on Soviet sgraffito and ancient Kazakhstani petroglyphs.

In Almaty, there's an impression of a culture in transition that is conscious of its nomadic origins and cautiously trying to strip away the layers and centuries of colonial rule—first Ottoman, then Soviet. In the 1930s, Stalin's forced collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union led to the deaths of up to 1.5 million people, including predominantly ethnic Kazakhs. About twenty years later, Khrushchev initiated the Virgin Lands Campaign, aimed at drastically increasing food production by cultivating land mainly in Kazakhstan, but also in parts of Siberia and other regions. This changed Kazakhstan demographically and geographically enormously, with many Russian speakers settling there. Today, the world's longest land border runs between Kazakhstan and Russia, and any discussion of this turbulent past remains diplomatically sensitive.

In this context, there's considerable courage in opening the glittering AMA with a retrospective of artist Almagul Menlibayeva and also showing her critical video work about the Soviet atomic bomb test site Semipalatinsk in the Kazakhstani steppe. Even the exhibition of significant international artists apparently underscores not only the museum's purchasing power, as suggested by Anselm Kiefer's monumental painting series made with thick layers of oil or lead. It bears the title "Questi scritti, quando verranno bruciati, daranno finalmente un po di luce" (These writings, when burned, will finally give a little light) and was acquired by the AMA directly after its presentation in 2022 at the Palazzo Ducale in Venice.

At the same time, all of Kazakhstan was gripped by violent protests against the government with many deaths. According to AMA director Meruyert Kaliveya, the social unrest at that time provided the impetus for the acquisition, saying the universal message of hope conveyed by the title appealed to them. It appears that political discourses are also being carefully conducted in Kazakhstan's newly founded art institutions, even if major international names must first help to publicly explore difficult topics.